On bell hooks and Feminist Blind Spots: Why Theory Will Not Set Us Free

One of the more frustrating things that accompanies publicly and proudly claiming feminism is the constant questioning of the integrity of my identity. Those who have no vested interest in the movement assault me with bad faith interrogations of my ideological commitment in the hope that they will prove to me and to themselves that I'm not who I say I am. They want me to admit that although I claim this identity, I am not feminist enough because of the music I enjoy, the clothes I wear, or the words I use -- that I might wear the t-shirt, but I'm not really a member.

These exchanges turn from bothersome to hurtful when initiated by women who also assert a feminist identity. They hope to make it clear that I have two options: cast aside that which offends or admit my inauthenticity. But I refuse to bow to the gatekeepers because this, too, is my birth right.

I do not deny that my feminism is imperfect. My feminism is messy because life happens in the gaps for which theory provides no cover.

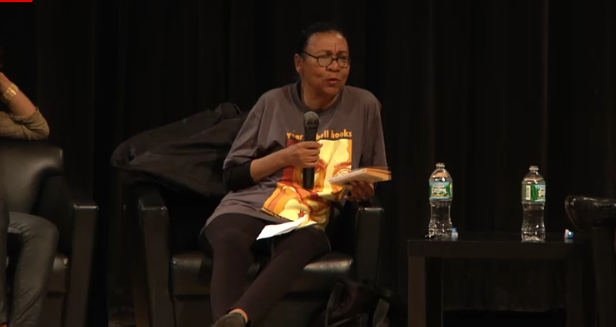

Last week, scholar bell hooks offered some quick thoughts on Beyonce that caused nothing short of an intra-feminist uproar.

"I see a part of Beyonce that is anti-feminist--that is assaulting," she said. "That is a terrorist in terms of impact on young girls." Hooks, earlier in the discussion, suggested that the superstar is a "slave" because of her use of oppressive systems for personal gain.

My admiration of bell hooks cannot be overstated, but she got it wrong here. And her comments expose the weaknesses of relying primarily on theory to shape a feminist ideal. We must encourage subversion of imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy, but that should not happen without acknowledgment that Black women must not only survive but find joy while navigating this world in our assaulted bodies. Grappling with these things that are often placed in conflict necessitates nuanced discussions of our lives and work.

Beyoncé does many things at once. And while, I too, find some of the most visible parts of her image and work to be regressive, a reading of Beyoncé that sees her only as objectification and collusion is a superficial one. It ignores the ways that she challenges mainstream notions of black womanhood and affirms women seeking to disentangle themselves from shame and domination.

Beyoncé's work and person does aid many Black women in coping with lived experiences in which they encounter intersecting oppressions. For example, A Black male friend told me recently that he credits the superstar for the devolving relations between Black Millennial men and women. He argued that her music has made us "too confident." Of course he's wrong, but this Black man can see that since the days of Destiny's Child, this particular brand of r&b/pop often advocates resistance to domination by Black men in the forms of self-confidence, sisterhood, financial independence, and sexual assertiveness. The push back to that occurs when women recite the lyrics or apply these ideas in their interpersonal relationship is a threat to Black Male Privilege. She speaks directly to women's experiences with double standards and sexism in undeniably black sounds. Through the years, she has also been an unfortunate advocate of respectability ("Nasty Girl"), but again, you do not have to be perfect to be of value.

Even a sexuality that you find vulgar or offensive can be a liberated sexuality. And for some of us, Bey is a welcome counter to the ubiquitous images of the shamed and/or degraded Black female body. That the space is so narrow that people who call themselves progressive have no hesitation in equating a performer to a prostitute is a reflection of the need for a reassessment of the societal baggage Black women must carry on their bodies at all times. Demonizing this woman to deny her bodily autonomy for the sake of "young girls" is reductive. We all need avenues to engage with our sexualities, and your path might not look like mine.

bell hooks critique was not radical but painfully conservative. For too long Black women have practiced a politics of containment wherein we have been instructed to conceal our bodies for fear that they will work in service of imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. But fear and shame do not encourage resistance.

Interestingly, when, during the discussion, Janet Mock claimed use of glamour as a source of power, she was not met with any push back. "For me to pretty myself up in whatever way I want...to claim my body...there's power in claiming that space," she explains. "Especially in a world that says I shouldn't exist...I will do that for myself."

Certainly Janet, as a trans woman, understands the benefits of embracing an aesthetic that does not threaten dominant ideals. Glamour can be seen as a byproduct of patriarchal and white supremacist definitions of beauty, but in Janet's choice we see her self-determination rather than capitulation. I can see her resistance and celebrate her visibility because I recognize that she is thriving in a system in which she was never meant to survive. Sadly all women, certainly not Beyoncé, do not get that same consideration. But it seems skewering the actor instead of the system is OK when that actor has done too well.

No feminist is above critique, and when we err, correction should follow. But when I get things wrong, you don't get to invalidate my identity. No woman deserves that erasure. When that critique seeks to demean and devalue a Black woman for fighting to be seen--for not prioritizing her life on your terms, it becomes a violence.

A brilliant woman once said feminism is for everyone, but there exists a the chasm between those who refuse to acknowledge the inherent "messiness" of this fight and those of us who can admit to still learning and growing in our identities. In all or nothing discussions about a feminist ideal, we lose sight of many women's realities. I don't need a feminism that excels in rhetoric but fails in practice. I'm invested in a feminism that works -- a feminism that is resilient and complex.

My feminism is complicated. It needs both bell and Bey to thrive. I needed theory as a blueprint, but it often fails as a compass.

Can I live?

Kimberly Foster is the founder and editor of For Harriet. Email or Follow @KimberlyNFoster

No comments: