The Black Women Pioneers of the Education Desegregation Movement

In honor of the 60th anniversary of the historic Brown v. Board of Education ruling, For Harriet would like to celebrate the Black Women who spearheaded the civil rights movement through their commitment to education integration and equality. Their lives and courage have had a lasting impact.

Ruby Bridges

Ruby Bridges was born in 1954 in Mississippi, before her family moved to New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1960, New Orleans was court ordered to desegregate all schools. Bridges became the first Black child to attend an all-white school, William Frantz Elementary School. The NAACP encouraged her parents to integrate their daughter after passing a test to prove her intelligence was on par to attend school with white children.

Although six Black children were eligible to integrate to white schools, Bridges was the only one assigned to attend William Frantz. She had to be taken to school by federal marshals, to protect her from angry protestors. She worked one-on-one with her first grade teacher, Mrs. Henry, for the entire year.

Bridges went on to business school and worked as a travel agent before leaving work to focus on raising her family. In 1993, she became a volunteer at William Frantz Elementary School. Now 59, is a notable activist and runs the Ruby Bridges Foundation, whose mission is to promote tolerance and respect. She tours around the country, giving speeches about her experiences. She still lives in New Orleans today.

(Sources: Wikipedia and RubyBridges.com)

Charlayne Hunter Gault

Charlayne Hunter was born in South Carolina in 1942. Due to her father’s career in the military, her family moved around a lot. However, she and her younger brothers eventually settled in Atlanta, where they were primarily raised by her mother and maternal grandmother. She credits her grandmother for inspiring her early interest in reading and the newspaper.

In 1959, she applied to the University of Georgia, but was denied admittance, so she attended Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan. However, every semester she would submit her application the University of Georgia with the help of the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund.

Bridges went on to business school and worked as a travel agent before leaving work to focus on raising her family. In 1993, she became a volunteer at William Frantz Elementary School. Now 59, is a notable activist and runs the Ruby Bridges Foundation, whose mission is to promote tolerance and respect. She tours around the country, giving speeches about her experiences. She still lives in New Orleans today.

(Sources: Wikipedia and RubyBridges.com)

Charlayne Hunter Gault

Charlayne Hunter was born in South Carolina in 1942. Due to her father’s career in the military, her family moved around a lot. However, she and her younger brothers eventually settled in Atlanta, where they were primarily raised by her mother and maternal grandmother. She credits her grandmother for inspiring her early interest in reading and the newspaper.

In 1959, she applied to the University of Georgia, but was denied admittance, so she attended Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan. However, every semester she would submit her application the University of Georgia with the help of the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund.

In early 1961, Judge William Bootle ruled that Hunter “qualified for… immediate enrollment at the University of Georgia”. Along with Hamilton Holmes, Hunter was one of the two first African-American students to enroll at the University of Georgia. Hunter was often the object of much hostility and aggression. However in 1963, she graduated and married fellow student Walter Stovall, a white man. They had a daughter, Susan, but divorced nine years later.

She would later go on to become an award-winning broadcast journalist, working in both broadcast and print journalism. Hunter worked for such esteemed journalism outlets as the New Yorker, New York Times, NPR, and CNN. Her work garnered her two Emmy awards as well as two Peabody awards. She currently lives in South Africa with her husband, Robert Gault. She has two children: Susan from her first marriage and Chuma from her second.

(Sources: Wikipedia and New Georgia Encyclopedia)

Vivian Malone Jones

Vivian Malone was born in 1942 in Mobile, Alabama. Both of her parents worked at Brookley Air Force Base and were involved in the Civil Rights Movement. Thus, Malone spent a lot of time volunteering for community-based organizations that promoted equality and an end to racial discrimination. Malone graduated from high school as a member of the National Honors Society.

She would later go on to become an award-winning broadcast journalist, working in both broadcast and print journalism. Hunter worked for such esteemed journalism outlets as the New Yorker, New York Times, NPR, and CNN. Her work garnered her two Emmy awards as well as two Peabody awards. She currently lives in South Africa with her husband, Robert Gault. She has two children: Susan from her first marriage and Chuma from her second.

(Sources: Wikipedia and New Georgia Encyclopedia)

Vivian Malone was born in 1942 in Mobile, Alabama. Both of her parents worked at Brookley Air Force Base and were involved in the Civil Rights Movement. Thus, Malone spent a lot of time volunteering for community-based organizations that promoted equality and an end to racial discrimination. Malone graduated from high school as a member of the National Honors Society.

She attended Alabama A&M University, where she received a degree in Business Administration in 1963. However, Alabama A&M had not been fully accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. To have a verified degree and continue pursuing accounting, she would need to transfer to another school.

In 1961, Malone was encouraged by a family friend to apply to the University of Alabama in Mobile, as part of an attempt to desegregate the school. Along with 200 other Black students, her application was denied. However, despite this setback and threats of violence, Vivian remained undeterred. She began working with the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund. In 1963, Judge Harlan Grooms decided in favor of Vivian and fellow student, James Hood, that they were eligible to attend the University of Alabama due to the Supreme Court ruling of Brown vs. Board of Education.

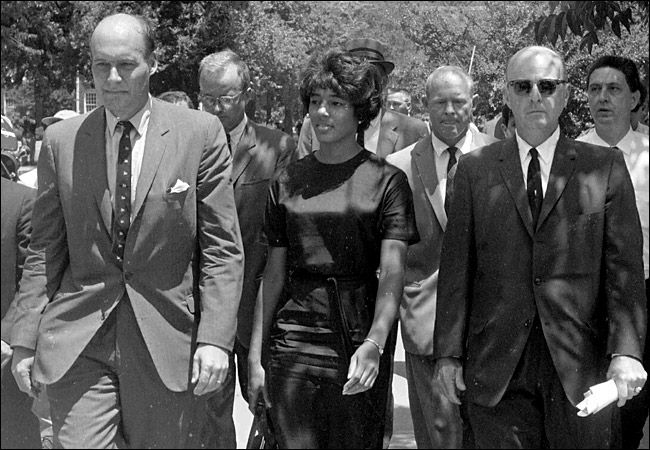

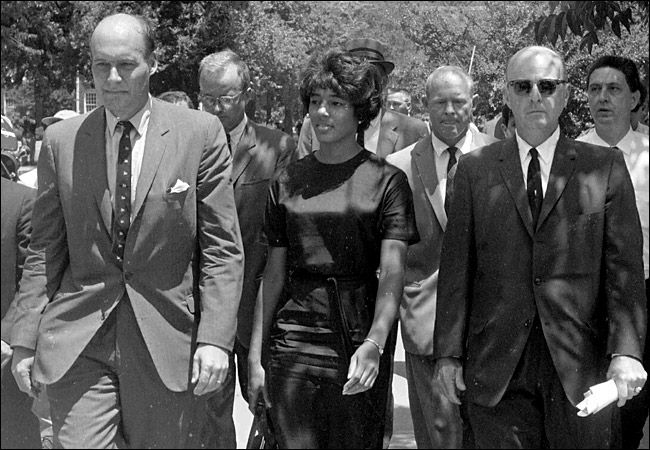

In 1963, Vivian and Hood were escorted to their first day at the University of Alabama by a motorcade and U.S. Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach. They were stopped by Alabama Governor George Wallace from enrolling. Later, President Kennedy would intervene, allowing Malone and Hood to enroll in classes. In 1965, she became the first African-American student to graduate from the University of Alabama with a degree in business management.

Vivian Malone married Mack Jones, a physician, and went on to work for the U.S. Department of Justice before getting a master’s degree in public administration from George Washington University. She continued to work for the government, focusing on civil rights and equality issues, until her retirement in 1996. She also became she first recipient of the George Wallace Family Foundation’s Lurleen B. Wallace Award of Courage in 1996. She passed away in 2005.

(Sources: Wikipedia and American National Biography)

The McDonogh Three

In 1960, all New Orleans public schools were issued to desegregate by court order, almost six years after the Supreme Court ruling of Brown vs. Board of Education. Leona Tate, Tessie Prevost, and Gail Etienne had all attended Black-only schools in New Orleans’ Ninth Ward. They were zoned to attend previously all-white McDonogh No. 19 Elementary School.

In 1961, Malone was encouraged by a family friend to apply to the University of Alabama in Mobile, as part of an attempt to desegregate the school. Along with 200 other Black students, her application was denied. However, despite this setback and threats of violence, Vivian remained undeterred. She began working with the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund. In 1963, Judge Harlan Grooms decided in favor of Vivian and fellow student, James Hood, that they were eligible to attend the University of Alabama due to the Supreme Court ruling of Brown vs. Board of Education.

In 1963, Vivian and Hood were escorted to their first day at the University of Alabama by a motorcade and U.S. Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach. They were stopped by Alabama Governor George Wallace from enrolling. Later, President Kennedy would intervene, allowing Malone and Hood to enroll in classes. In 1965, she became the first African-American student to graduate from the University of Alabama with a degree in business management.

Vivian Malone married Mack Jones, a physician, and went on to work for the U.S. Department of Justice before getting a master’s degree in public administration from George Washington University. She continued to work for the government, focusing on civil rights and equality issues, until her retirement in 1996. She also became she first recipient of the George Wallace Family Foundation’s Lurleen B. Wallace Award of Courage in 1996. She passed away in 2005.

(Sources: Wikipedia and American National Biography)

The McDonogh Three

In 1960, all New Orleans public schools were issued to desegregate by court order, almost six years after the Supreme Court ruling of Brown vs. Board of Education. Leona Tate, Tessie Prevost, and Gail Etienne had all attended Black-only schools in New Orleans’ Ninth Ward. They were zoned to attend previously all-white McDonogh No. 19 Elementary School.

On November 14, 1960, all three girls were escorted by federal marshals to McDonogh, while Ruby Bridges attended William Frantz Elementary School. They were met by angry and protesting crowds. And thus, for two years, were the only students educated at McDonogh. They were not allowed to have recess outside or use the water fountains, as officials feared they would be in danger. They eventually left McDonogh to enroll at the newly integrated T.J. Semmes Elementary School, with twenty other Black students.

Leona Tate now has the Leona Tate Foundation for Change, whose mission is to promote racial equality through education. Tessie Prevost Williams went on to work at the Louisiana State University School of Dentistry. She still gives speeches along with Tate and Etienne-Netters to talk about their experiences. Gail Etienne-Netters went on to help integrate Francis T. Nicholls High School by attending with Tate.

(Sources: Wikipedia and Nola.com) Photo credit: Ted Jackson, Times Picayune

Barbara Rose Johns

Barbara Rose Johns was born in New York City in 1935. She grew up in Prince Edward County, Virginia. Her uncle was the prominent civil rights leader and preacher, Reverend Vernon Johns. His influence helped spark her interest in Black history and the Civil Rights Movement. She attended Moton High School, an all-Black segregated school in Farmville, Virginia. The resources and facilities of the school were of poor quality, in addition to the school being overcrowded.

In 1951, at age 16, she organized a student strike with fellow classmates due to the unequal conditions of Moton compared to the all-white high school across town. On April 23rd, Johns gave a speech to fellow students at an unauthorized school assembly. With her classmates, she marched to the county courthouse to bring awareness of the unfair conditions of Moton.

Leona Tate now has the Leona Tate Foundation for Change, whose mission is to promote racial equality through education. Tessie Prevost Williams went on to work at the Louisiana State University School of Dentistry. She still gives speeches along with Tate and Etienne-Netters to talk about their experiences. Gail Etienne-Netters went on to help integrate Francis T. Nicholls High School by attending with Tate.

(Sources: Wikipedia and Nola.com) Photo credit: Ted Jackson, Times Picayune

Barbara Rose Johns

Barbara Rose Johns was born in New York City in 1935. She grew up in Prince Edward County, Virginia. Her uncle was the prominent civil rights leader and preacher, Reverend Vernon Johns. His influence helped spark her interest in Black history and the Civil Rights Movement. She attended Moton High School, an all-Black segregated school in Farmville, Virginia. The resources and facilities of the school were of poor quality, in addition to the school being overcrowded.

In 1951, at age 16, she organized a student strike with fellow classmates due to the unequal conditions of Moton compared to the all-white high school across town. On April 23rd, Johns gave a speech to fellow students at an unauthorized school assembly. With her classmates, she marched to the county courthouse to bring awareness of the unfair conditions of Moton.

During the strike, Barbara and classmates sought help from the NAACP to file a suit for an integrated school system in Prince Edward County. When the federal court upheld segregation in Davis vs. Board of Prince Edward County, the NAACP sought appeal from the U.S. Supreme Court. The case, along with four others, became part of the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling as the only one initiated by student protest. Because of this, it has also been seen as an early prominent event for the Civil Rights Movement.

Barbara Rose Johns moved to Montgomery, Alabama, soon after. She attended Spelman College in Atlanta and Drexel University in Philadelphia. She married Reverend William Powell, had five children, and remained committed to education as a librarian. She died in 1991.

(Sources: Wikipedia and Robert Russa Moton Museum) Photo source

Zelma Henderson

Zelma Henderson (née Hurst) was born in Kansas in 1920. Her parents worked in agriculture, growing wheat and raising livestock. Hurst attended integrated elementary schools, as Kansas law only mandated towns with populations of 15,000 or more to have segregated schools.

In 1940, she moved to Topeka, Kansas, where encountered blatant racism and discrimination. She attended the segregated Kansas Vocational School for cosmetology. She could only find domestic work due to her race. She married her husband, Andrew Henderson, in 1943 before opening a salon and having two children, Donald and Vicki.

Her children were made to attend an all-Black school across town. This angered Henderson, as she had attended integrated schools in the smaller towns where she grew up. In 1950, she became involved in the school integration movement with the local chapter of the NAACP, as part of a lawsuit against the Topeka school board.

Barbara Rose Johns moved to Montgomery, Alabama, soon after. She attended Spelman College in Atlanta and Drexel University in Philadelphia. She married Reverend William Powell, had five children, and remained committed to education as a librarian. She died in 1991.

(Sources: Wikipedia and Robert Russa Moton Museum) Photo source

Zelma Henderson

Zelma Henderson (née Hurst) was born in Kansas in 1920. Her parents worked in agriculture, growing wheat and raising livestock. Hurst attended integrated elementary schools, as Kansas law only mandated towns with populations of 15,000 or more to have segregated schools.

In 1940, she moved to Topeka, Kansas, where encountered blatant racism and discrimination. She attended the segregated Kansas Vocational School for cosmetology. She could only find domestic work due to her race. She married her husband, Andrew Henderson, in 1943 before opening a salon and having two children, Donald and Vicki.

Her children were made to attend an all-Black school across town. This angered Henderson, as she had attended integrated schools in the smaller towns where she grew up. In 1950, she became involved in the school integration movement with the local chapter of the NAACP, as part of a lawsuit against the Topeka school board.

Along with Oliver Brown, she served as one of 13 plaintiffs in the case, who the federal court ruled against in favor of segregation. They appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court as part of Brown vs. Board of Education with five other cases from other states. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled to end segregation in public schools in 1954.

Henderson continued to live in Topeka for the rest of her life, often giving media interviews about her involvement and thoughts on the case. She died in 2008, the last surviving plaintiff in the Brown v. Board case.

(Sources: Wikipedia and New York Times) Photo Credit: Anthony S. Bush/topeka capital journal

(Source: Wikipedia) Photo credit: University Communications photo by David Tisdale

Daisy Bates and the Little Rock Nine

Daisy Bates was an activist, journalist, and civil rights leader involved in the Little Rock Integration Movement. She was born Daisy Gatson in Arkansas in 1914. When she was very young, her mother was raped and murdered by three white men. Shortly after, her father died, so she was raised by family friends.

After the integration of Central High School, Bates continued her civil rights activism. She and her husband closed down their newspaper in 1959. She worked in Washington, D.C. for a few years before returning to Little Rock to continue her work in the community in the 1960s. After her husband passed away in 1980, she restarted their newspaper. Daisy Bates passed away in 1999.

(Sources: Wikipedia, NPR, and Biography.com) Photo credit: Courtesty of PBS

Henderson continued to live in Topeka for the rest of her life, often giving media interviews about her involvement and thoughts on the case. She died in 2008, the last surviving plaintiff in the Brown v. Board case.

(Sources: Wikipedia and New York Times) Photo Credit: Anthony S. Bush/topeka capital journal

Gladys Hedgepeth and Berline Williams

In September 1943, Leon Hedgepeth and Janet Williams were prohibited from entering an attending Junior School No. 2, their neighborhood school in Trenton, New Jersey. The principal told them the school was “not built for Negroes”. Instead, they were forced to attend the all-Black school, New Lincoln School, despite it being further away from them. Their mothers, Gladys Hedgepeth and Berline Williams, were outraged by the blatant discrimination and filed a lawsuit against the Trenton School System.

In 1944, the New Jersey Supreme Court sided with Hedgepeth and Williams, stating that it was “unlawful” to bar Black children from attending public schools because of their race. The case became a precedent for the Brown v. Board of Education ruling ten years later in 1954. It also continued to influence many Affirmative Action and equal opportunity policies in New Jersey’s education system, as well as the eradication of laws supporting discrimination in New Jersey.

Today, the school their children integrated to has been renamed Hedgepeth-Williams Middle School.

(Sources: Wikipedia and Hedgepeth-Williams.org) Pictured: Berline Williams, Attorney Robert Queen, Leon Williams, Gladys Hedgepeth, Janet Hedgepeth Photo source

Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher

Ada Lois Sipuel was born in Chickasha, Oklahoma, in 1924. She graduated as valedictorian of her high school class and attended Langston University in 1942, where she married her husband, Warren Fisher, before graduating in 1945.

She planned on challenging the segregation of the University of Oklahoma with her brother, as they both planned on attending law school there. However, her brother decided to attend Howard University Law School. Fisher decided to continue challenging segregation, applying to the University of Oklahoma in 1946. She was denied admittance because of her race.

In September 1943, Leon Hedgepeth and Janet Williams were prohibited from entering an attending Junior School No. 2, their neighborhood school in Trenton, New Jersey. The principal told them the school was “not built for Negroes”. Instead, they were forced to attend the all-Black school, New Lincoln School, despite it being further away from them. Their mothers, Gladys Hedgepeth and Berline Williams, were outraged by the blatant discrimination and filed a lawsuit against the Trenton School System.

In 1944, the New Jersey Supreme Court sided with Hedgepeth and Williams, stating that it was “unlawful” to bar Black children from attending public schools because of their race. The case became a precedent for the Brown v. Board of Education ruling ten years later in 1954. It also continued to influence many Affirmative Action and equal opportunity policies in New Jersey’s education system, as well as the eradication of laws supporting discrimination in New Jersey.

Today, the school their children integrated to has been renamed Hedgepeth-Williams Middle School.

(Sources: Wikipedia and Hedgepeth-Williams.org) Pictured: Berline Williams, Attorney Robert Queen, Leon Williams, Gladys Hedgepeth, Janet Hedgepeth Photo source

Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher

Ada Lois Sipuel was born in Chickasha, Oklahoma, in 1924. She graduated as valedictorian of her high school class and attended Langston University in 1942, where she married her husband, Warren Fisher, before graduating in 1945.

She planned on challenging the segregation of the University of Oklahoma with her brother, as they both planned on attending law school there. However, her brother decided to attend Howard University Law School. Fisher decided to continue challenging segregation, applying to the University of Oklahoma in 1946. She was denied admittance because of her race.

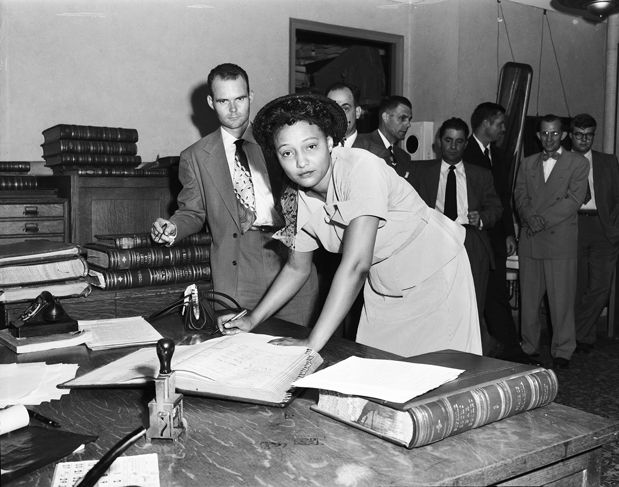

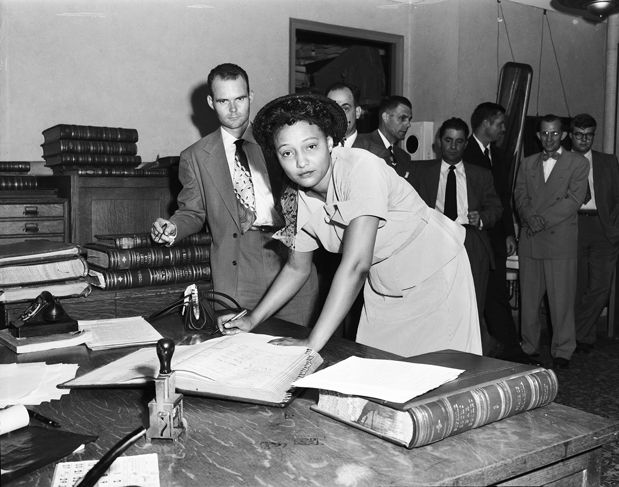

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in her favor in Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma, stating that education for Black students must be equal to that of white students. To comply with this ruling, a school of law was created at Langston University. However, further legal action was pursued to prove that this school was inferior to the University of Oklahoma’s law program.

In 1949, Fisher became the first African-American admitted to attend the University of Oklahoma’s law school while pregnant with her first child. Despite her classmates and professors welcoming her, she had to sit in separate chairs marked “colored” in classes and had to eat in a separate part of the cafeteria.

In 1951, she graduated with a law degree and began practicing in her hometown. She also worked as a professor at Langston University. In 1992, she was appointed to the Oklahoma University’s Board of Regents. She passed away in 1995.

(Sources: Wikipedia and Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture) Photo source

Gwendolyn Elaine Armstrong

Gwendolyn Elaine Armstrong became one of the two first African-American students to attend the University of Southern Mississippi at Hattiesburg (USM) in 1965, along with Raylawni Branch, despite the unsuccessful attempts of Clyde Kennard to enroll at USM in the 1950s.

In 1951, she graduated with a law degree and began practicing in her hometown. She also worked as a professor at Langston University. In 1992, she was appointed to the Oklahoma University’s Board of Regents. She passed away in 1995.

(Sources: Wikipedia and Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture) Photo source

Gwendolyn Elaine Armstrong

Gwendolyn Elaine Armstrong became one of the two first African-American students to attend the University of Southern Mississippi at Hattiesburg (USM) in 1965, along with Raylawni Branch, despite the unsuccessful attempts of Clyde Kennard to enroll at USM in the 1950s.

After graduating from Rowan High School in Hattiesburg, the NAACP worked with her to gain entry to the segregated USM. Although the University’s administration had previously fought attempts to integrate the school, they helped extensively with both women’s admission and enrollment.

Armstrong was appointed a faculty mentor, as well as protection from the on-campus police. Because of this, she experienced little hostility. She studied music, participating in USM’s championship-winning choir, before pursuing a brief singing career after leaving the University of Southern Mississippi.

(Source: Wikipedia) Photo credit: University Communications photo by David Tisdale

Daisy Bates and the Little Rock Nine

Daisy Bates was an activist, journalist, and civil rights leader involved in the Little Rock Integration Movement. She was born Daisy Gatson in Arkansas in 1914. When she was very young, her mother was raped and murdered by three white men. Shortly after, her father died, so she was raised by family friends.

She married L.C. Bates, a journalist, in 1942 and together they moved to Little Rock. In Little Rock, they began the Arkansas State Press, a weekly newspaper for the Black community. And in 1952, Bates became the president of the Arkansas chapter for the NAACP.

After the Supreme Court ruled to desegregate school in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, Bates and her husband became heavily involved in the school integration movement in Arkansas. In 1957, she helped to recruit nine Black students to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. They would become known as the “Little Rock Nine”.

When they first attempted to enter Central High on September 4th, Governor Orval Faubus ordered the National Guard to turn them away. The children did not attempt to return to school again until September 23rd. There was a mob of irate, violent protestors outside the school as the children were escorted by police, so they were removed from the school. Finally, on September 25th, they were allowed to enter the school with help from the U.S. military. During this time, Bates served as a spokeswoman and advocate for the Little Rock Nine. She continued to remain close to them and offered her support during their time at Central High.

After the integration of Central High School, Bates continued her civil rights activism. She and her husband closed down their newspaper in 1959. She worked in Washington, D.C. for a few years before returning to Little Rock to continue her work in the community in the 1960s. After her husband passed away in 1980, she restarted their newspaper. Daisy Bates passed away in 1999.

(Sources: Wikipedia, NPR, and Biography.com) Photo credit: Courtesty of PBS

Constance Baker Motley

Constance Baker Motley was a civil rights activist, lawyer, and public official. She was born in Connecticut in 1921. Her parents were immigrants from the West Indies and she was one of twelve children.

Constance Baker Motley was a civil rights activist, lawyer, and public official. She was born in Connecticut in 1921. Her parents were immigrants from the West Indies and she was one of twelve children.

During high school, she became involved in the civil rights movement and decided to study law. She attended Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, before transferring to New York University. She graduated with her bachelor’s degree from NYU in 1943 before enrolling in Columbia University’s law school. She graduated with her law degree in 1946.

She began working as a clerk for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, along with other civil rights attorneys like future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and Jack Greenberg. She eventually became an associate attorney with the NAACP Defense Fund, working on several prominent civil rights cases herself.

In 1950, Motley helped write the original case filing for Brown v. Board of Education. And in 1962, she became the first African-American woman to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court in Meredith v. Fair, successfully winning James Meredith’s case to be the first Black student to attend the University of Mississippi. In total, she won nine out of ten cases argued before the Supreme Court, representing many involved in the civil rights movement including Martin Luther King, Jr.

Motley went on to become the first African-American woman to be elected to New York’s State Senate in 1964, as well as the first African-American woman to be elected a federal court judge in 1966. She held this position until her death in 2005.

(Sources: Wikipedia and Biography.com) Photo source

In 1950, Motley helped write the original case filing for Brown v. Board of Education. And in 1962, she became the first African-American woman to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court in Meredith v. Fair, successfully winning James Meredith’s case to be the first Black student to attend the University of Mississippi. In total, she won nine out of ten cases argued before the Supreme Court, representing many involved in the civil rights movement including Martin Luther King, Jr.

Motley went on to become the first African-American woman to be elected to New York’s State Senate in 1964, as well as the first African-American woman to be elected a federal court judge in 1966. She held this position until her death in 2005.

(Sources: Wikipedia and Biography.com) Photo source

Michelle Denise Jackson is a writer, performer, and storyteller from Southern California. She has performed in Southern California, New York, New Jersey, Michigan, and Washington, D.C. For more information, visit her website at michelledenisejackson.com.

No comments: