A Domestic Dream: Re-imagining Black Motherhood

The seeds of my feminism were planted early. Women predominate my childhood memories. And not just any women: strong, Black women. Sisters who did it for themselves. The kind of women Lil Boosie writes songs about (I-N-D-E-P-E-N-D-E-N-T). These women instilled in me the value of self-sufficiency and hard work. They taught me what it meant to navigate the world as a Black woman in a racist, sexist society.

As a child, it was difficult to reconcile my own mother’s overburdened existence with the cushy lives that the mothers of my primarily white, suburban peers led. Their moms didn’t have to work. They attended every field trip, performance, and PTA meeting. They brought cupcakes to school just because. I remember a couple of the most active moms vividly. They were the Hall of Famers.

The Superstar Moms were almost always white. I never wondered why; I simply reasoned that these were just not things Black women did. (My nonexistent understanding of the structures of oppression that limit the agency of women of color as well as poor women shaped that logic.)

My mother regularly engaged my teachers--making sure we felt her presence, but I suspect she would not have been fulfilled by the life of a PTA MVP. She embodies a relentless determination that facilitated her professional success, and she did it with far fewer resources than many of her colleagues. Her existence was rooted in resistance. The balancing act was a tribute to her foremothers.

At 22, I’m just beginning to imagine my own future as a multi-hyphenate woman. I share my mother’s ambition, but I cannot see myself following the same path. Black women have long taken pride in our ability to be masters of all domains, but younger generations of women, myself included, seem to be rethinking that legacy. Perhaps “mom” is the only title that interests me.

Escaping The System

The global economic system relies on the exploitation of women’s labor, particularly that of minority women; thus, many Sisters face economic instability that prevents them from dropping out of the workforce for any period of time to focus exclusively on childcare. These women are, of course, vilified and painted as the stereotypical Matriarch Patricia Hill Collins outlines.

Questioning your predetermined societal roles requires power. We derive power from capital, so options for women with little access remain limited. As Black women have made gains up the socioeconomic ladder, we are provided more freedom to choose our roles. My mother, with her education and income, chose career woman. However, women like me are contemplating alternate courses.

Would I be willing to forgo creature comforts for a life of diapers and Disney? Perhaps. Natasha Smith, an Ivy-league educated former attorney, made the sacrifice. After an unexpected pregnancy, she rearranged her life:

I ate through my savings, and eventually moved in with family so that I could be the kind of mother I wanted. I worked (coaching figure skating) part-time. I've witnessed all of Nate's firsts. This is what life is about. I'm shaping who he is as a person. This is more important to me than having material things.At the moment*, I have a deep desire to be a hands-on-mom of 4 (yes, 4) kids. I know better than to internalize the myth of the Working Mom Who Did It All With Ease perpetuated in 80s TV sitcoms. Clair Huxtable, though near and dear to us all, was a fictional character. Oprah, who has no children, once said, “You can have it all. Just not all at once.” As usual, Oprah is right.

Embracing motherhood and domesticity requires mediating career ambitions. This thought, however, fills me with angst.

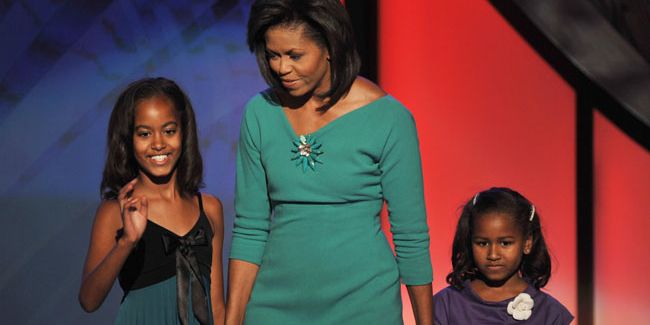

The (Michelle) Obama Effect

African American women have opted for child-rearing over work for generations, but the choice has yet to be normalized in our community. We celebrate the women who break barriers of industry with tributes like Black Girls Rock, but what about the women who define themselves by their role as a mother. They don’t even get romanticized, fictional portrayals. Black stay-at-home mothers have a single, highly visible role model: Michelle Obama.

The First Lady has taken her licks from feminists for touting her role as “Mom In Chief,” but her self-definition is cause for celebration. Embracing the beauty of domesticity requires a rejection of the patriarchal/capitalist tendency to diminish the value of motherhood.

Despite the fact that it produces no tangible goods, motherhood is work. Seeing Michelle Obama devote her sweat equity to her children presents a major shift in the way the general public perceives Black womanhood. Mammy is out. Mommy is in.

The Double Standard

In order to pursue motherhood full time, one needs the support of their partner and/or community. There exists within Black America significant opposition to employable Black women taking to the home. Jolene Ivey is a co-founder of Mocha Moms, a community for Black mothers who stay at-home. She laments, “Devoting full time to motherhood is considered a waste of education by many in the black community.”

Women who make the choice are explicitly told they are lazy. Detractors echo my sentiments from my childhood they say, “Staying at home is for white women.” According to Ivey:

The fact that, historically, black women have rarely had the luxury to choose not to work has helped to enforce an expectation that we must work. Black mothers who choose to stay home sometimes face particularly harsh judgment, as if stepping away from our professional degrees and careers is a thoughtless slap at our ancestors, who endured back-breaking, knuckle-skinning work for us to have the opportunities that we have today.Conversely, white stay-at-home moms are lionized. It is an unfair double standard that restricts our potential for self-actualization.

African American women are doing what we have done time and again: re-imagining Black womanhood. By accepting more possibilities, we deconstruct racist stereotypes. We need be neither welfare queens nor domestic goddesses. What we desperately need is the opportunity to mold our family lives to suit our individual needs and desires without cultural constraints or societal judgements.

Kimberly Foster is the Editor and Publisher of For Harriet. Email her at Kimberly@ForHarriet.com with comments or find her on Twitter.

No comments: