No Better Than You: Light-Skinned And Still Black

My father’s skin is a rich cocoa-brown color, and my mother is fair-skinned with light brown freckles, and natural red highlights in her hair. Her great-grandmother, Sara, was the daughter of a slave woman and her master. In a photo I saw of her, she appeared white and had braids that hung down to the center of her chest. Because she married a man who was also the child of his master, her daughter (my great-grandma Ethel) was fair-skinned as well.

As children, my sisters and I thought our great-grandmother was white, but she was quick to correct us and anyone else who made that assumption. She told us that the slave master got in bed with the slaves, and that’s why she was so light. Her genes were more dominant than the brown-skin genes in my lineage; therefore, I came out tan-complexioned with a very soft texture of hair. Like my great-grandmother, I have never identified with being anything but Black, and didn’t think my skin color made me any different than any darker skinned person. It wasn’t until I became an adult that I realized some people had labeled me as “not Black enough” and expected me to behave a certain way based on the tone of my skin.

Even as a child I was Afrocentric. The Kenya and Iman dolls were my favorite and I did not want anything else. My father and I would sit and watch Black history specials on television, and I often tried to re-enact Alvin Ailey’s Revelations in the attic of our home. Whenever my mother and I visited the home of an older family friend, I would sit on the couch for hours and read her Ebony magazines from the sixties and seventies. I loved Black history, Black art and Black culture because I saw myself in it. We were a middle class family with middle class values, but we all spoke Ebonics. I grew up in the heart (hood) of Detroit, and felt like the people around me were a part of my family. I thought it was hilarious when other Black people asked me “What you mixed with?” I would reply “Black!” I couldn’t understand why they saw me any differently than themselves. It wasn’t until I was in my twenties that I learned that some people perceived me as white, and expected me to behave in a “bourgeoisie” manner because of the color of my skin and texture of my hair.

I started hearing comments like “Well you’re not Black anyway,” and “White women like you don’t have to deal with that.” A friend once said to me “When I first met you I expected you to act light-skinned.” I was both appalled and confused. I asked him what it meant to “act” light- skinned. He said acting light-skinned was acting uppity and snobbish, as if I were from a wealthy suburb. My younger sister, who is even lighter than I and whose hair is down to her buttocks, often comes to me with stories of being shunned by brown-skinned women and hearing snide remarks regarding her appearance. For both of us, these kinds of situations are hurtful and confusing. Our father and grandmother are brown-skinned, and we have many aunts, uncles and cousins who are brown-skinned as well. Perhaps we are a bit naïve, but these assumptions caught us off guard: we truly see no difference between ourselves and anyone of darker skin color.

I had been stereotyped and the victim of prejudice. This prejudice was not from people of a different ethnicity than me, but from people of my own ethnicity. This kind of prejudice made me feel excluded from something I loved and found my identity in. It was as if there was a reversed brown paper bag test that qualified me to call myself Black. I studied African-American history in college, so I am well aware of why these prejudices exist. A system of privilege, based on skin color, was established and perpetuated in the history of this country. During slavery, light-skinned slaves were “house niggers” and brown-skinned slaves were “field niggers.”

After slavery, a light complexion was necessary for Blacks to work some high-end jobs, and often provided access to other valuable opportunities. As a result, and one of the reasons why light- complexioned people are stereotyped as “uppity,” some of these privileged, light-complexioned Blacks took their status to the head. My father, who grew up in the fifties and sixties, was denied membership to a neighborhood club as a boy because he couldn’t pass the brown paper bag test. My grandmother, who is also brown-skinned, was ostracized and called names by fairer-skinned relatives. This system of inclusion and exclusion deemed light skin and soft hair better than brown skin and thick hair, and some people really believe it. There is a long history of internal racism within the Black community, but it does not have to continue to exist.

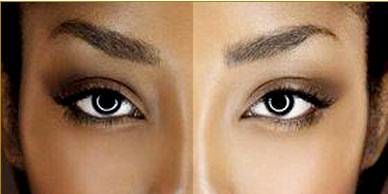

As a high school teacher, I often hear comments like “I only like light-skinned girls” or “I only like dark-skinned girls.” I’ve even heard “Dark-skinned girls are mean” and “Light-skinned girls think they all-that!” There are few things that irritate me more than comments like these, and I am quick to stand on my soapbox and give them a lecture about stereotypes and internal racism. Their comments, however, have helped me to see that the light-skinned/dark-skinned issue is very much alive and affects both adults and children. I tell them that the only thing that makes us different is the amount of melanin in our skin, or to state it more plainly, “the slave master got in bed with the slaves and that’s why I’m so light” as my great-grandmother would say. It is as simple as that. We are all brothers and sisters with many of the same experiences and struggles. Let’s embrace each other and ignore the lies that dominant society has told us about skin color and hair texture. Let’s take what was meant for evil, and destroy it.

Charday Ward is a freelance writer, playwright, teacher and founder and director of a mentoring organization in Detroit, Michigan. Follow her blog at bconscious.tumblr.com and on Twitter @IamChardayRenee

No comments: