African-American Heroes: Are We Being Told the Whole Story?

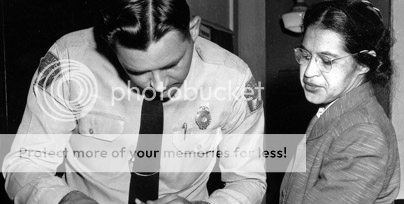

The story goes something like this: On a cold afternoon in Montgomery, Alabama circa 1955, a little feeble black woman just so happened to the spark the Civil Rights Movement when she refused to give up her seat at the front of a bus to a White man. She was a seamstress with worn out and tired feet—so tired that maybe her sense of decorum had been temporarily altered. There was no way she could get up from that seat, so an arrest had to happen.

That’s the story so many children learn about the “Mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” Rosa McCauley Parks. It’s the same story I was told through documentaries, illustrated children’s books and black history month programs over 20 years ago. Time and research have proven that we’ve only gotten the abridged version.

Parks’s place in history wasn’t coincidental, but in fact, intentional and directed. Her involvement in the Civil Rights Movement wasn’t so much calculated by the NAACP, as it was a personal goal.

Danielle McGuire, Ph.D., unveils Parks’ life before that fateful day on a Montgomery city bus in her book, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance-- A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power

.

.Parks was raised by her grandparents in Abbeville, Alabama and was strongly influenced by her grandfather, a follower of Marcus Garvey’s “Back to Africa” movement. Rather than meek and quiet though, McGuire describes Parks as “a militant race woman, a sharp detective, and an antirape activist.”

Always interested in race relations and civil rights, Parks saw many injustices, but the rape of Recy Taylor in 1944, more than a decade before the Montgomery Bus Boycott, prompted her to take immediate action. Taylor, a 24-year-old wife and mother, was raped by a group of white men in Abbeville and left on the street. An official arrest was not made, despite evidence. Parks and other leaders rallied together against the social injustice until it eventually became a national outrage. Her efforts included a full campaign aimed at Chauncey Sparks, Alabama governor with postcards and petitions for support she signed herself. Thereafter, thousands of letters poured into NAACP offices from African-American women who had also been raped by white men.

Bringing awareness to a hidden, but relevant issue, that is how Rosa Parks began her work in civil rights. And she knew exactly what she was doing.

McGuire says, “I started to think that Civil Rights that has been taught is slightly different when looked at through the lens of sexual abuse,” says McGuire, a Wayne State University professor whose book began as dissertation research.

“Americans like your heroes to be simple,” she says. “It’s easier to tell a simple story of a seamstress who was just tired. She was doing something outside of her gender roles and racial roles. This was a dynamic woman who had an appetite for justice.”

McGuire’s book brings an issue to the forefront. There seems to be a historical trend in African-American women being portrayed as one-dimensional beings. We are typecast as one of two stereotypes: pushovers or spitfires. Why aren’t our complex stories told in completion until years later, if ever? Consider Harriet Tubman, the publication’s namesake, and First Lady Michelle Obama—two different, yet vital historical figures in terms of era and mission.

Tubman, known for keeping a shotgun at her side to transition slaves to freedom through the Underground Railroad, was more than a “Moses,” but an intricate woman, whose life consisted of family turmoil, spirituality and love. In Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero, historian Kate Clifford Lawson writes, “The reality of Harriet Tubman’s life is more compelling than the partly fictionalized biography so familiar to schoolchildren.”

Why have we been satisfied with the mythical Tubman and why has her biography remained in the province of children’s literature? Although the myths are rooted in actual achievements, and serve to enhance the legend of Harriet Tubman, they do so at the expense of her real life story.”

First Lady Obama has the ability to write her own story thanks to increased visibility via the Internet. However, she, too, still fights through initiatives and programs, to have an identity other than the “President’s wife” or according to critics, the less than patriotic woman with the toned arms. Obama, who described herself as a “statistical oddity,” considering her upbringing in Newsweek’s 2008 profile, “Who Is Michelle Obama?” has the opportunity to show her multi-dimensional self. How delightful to see photographs of her campaigning on behalf of her husband or with her daughters, then working out with NFLers and children for her childhood obesity campaign.

But for those many unsung African-American heroes, living or deceased, who did not have the luxury of staff photographers, writers and even paparazzi, let us ponder on their stories, which may be more inspiring than the excerpts we’ve been taught. Though their impact is still felt, we don’t always have to take their places in history at face value. Do your research.

Alisha Tillery is a freelance writer living and working in Memphis, Tennessee. Her work has been published in UPTOWN Magazine, Honey Magazine, Clutch Magazine and Vibe Vixen Online. Though online publishing may be the new black, she still loves the rustle of printed magazine pages. She can be found ranting and writing at her personal blog, Because I Said So or at www.twitter.com/Alisha8151.

No comments: