A Framed, Faked Death: Response to Emmett Till, Lil Wayne and the Demise of Black Art

Since the 21st century commenced, claims of Black art’s alleged demise, from television to film to music, have littered the internet. I’ve witnessed impassioned conversations surrounding the state of Hip-Hop and rap music happen almost weekly on social networking sites and in barbershops alike. Quite often during these heated exchanges, participants on both sides of the debate agree to banish ‘90s babies to the back of the proverbial roundtable, deeming them unqualified to participate in music discourse for the sole fact that they’re existence began amidst the apparent decline of Hip-Hop.

Similar discussions occur around television and film. In too many instances, middle age Blacks have compared classic sitcoms like The Cosby Show and A Different World to reality television shows like the Real Housewives of Atlanta and Love & Hip-Hop, to me. They go on to use their comparisons as evidence of some sort of mass cultural decline, implicitly posing younger Black people as sole agents in this artistic genocide.

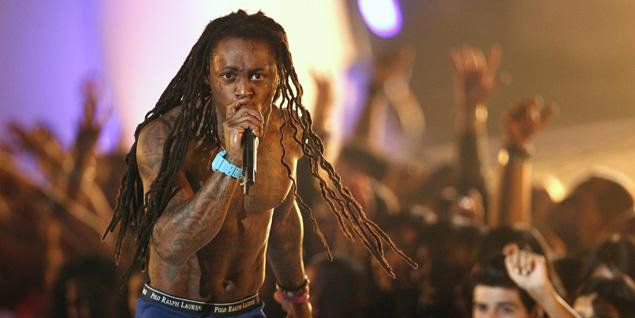

Then, Assita Camara reminded us of the artistic era we’re living in, music-wise, with a short essay critiquing Lil Wayne’s recent offense. The uproar revolves around Wayne’s metaphoric mention of Emmett Till’s death in conjunction with the act of having rough sexual intercourse. In an absolutely justified work, Camara discusses Lil Wayne’s lack of respect and abuse of cultural power. She even references Nicki Minaj’s “nappy-headed hoes” comment, and drops this jewel of a quote, “The influence that contemporary entertainers have is great power and as the saying goes, with great power comes great responsibility.”

I agree with Camara. But I’ve seen these types of critiques time and time again, and few make mention of capitalism, corporatism, or concentrated White ownership of Black culture—and these phenomena wreak havoc on Black culture in mainstream entertainment.

These arguments seem to focus on artists like Lil’ Wayne and Nicki Minaj as boasting complete agency and choice in their musical agendas. And don’t get me wrong—they hold a lot, obviously more than they make use of. However, as I’ve said before, it’s no coincidence that sexual violence and blatant attacks on Black hair come during socioeconomic conditions in which mainstream Black culture, from music to film, is owned and/or financed by wealthy White men.

In the racist, patriarchal, homophobic institution, it’s not “fate” that culturally offensive artists have some of the largest, most powerful platforms. It’s not an accident that, through White-owned avenues, lyrics that spite women, Black identity, and the LGBT community, receive the heaviest radio-play. It’s not under pure circumstance, that White teenagers jam the hardest to music that details—and mocks—very real instances of Black on Black crime, sexual violence, and reckless use of excess profit by a historically disadvantaged demographic.

White Supremacist culture awards behavior that distorts Black identity, with multi-million dollar record deals, film distribution contracts, and heft reality show agreements.

I may not like it, but I do not argue that these elements are not parts of Black culture. Indeed, they are. I don’t sit atop a high horse, desiring the eradication of every Black image that makes me cringe. Instead, I sit parallel to these events as they unfold, side-eyeing the entertainment industry for these acts being the only representative performances in mainstream media. Like Camara, I don’t need Lil Wayne to be Harry Belafonte. But the proverbial Harry Belafonte has disappeared from the world stage altogether. He didn’t walk off, either. He was fired.

White supremacist cultural hands reach so deep into every facet of Black life that even Black people and women support lyrics that encourage hatred of them.

In her response to a question about ghettoization, Radical Hearts gives a brief synopsis on the phenomena. She writes, “…Drugs and guns are injected, and the moral fabric begins to disintegrate. A counter-culture is adopted so that people living in the ghetto fully aware of their inability to escape can find counter means of measuring success and building self-esteem.” This counter-culture she references is debatably evidenced in the support of violent disparaging lyrics in mainstream Hip-Hop and rap music, by many young Black people living these same violent lyrics. Many of these young men and women align themselves with violent, patriarchal content in an effort to reaffirm their identities as non-agents of the state. Except, they are agents. Duped into supporting acts of “hood revolution”, they’re just swept into the capitalist-racist cycle that perpetuates the Black identity as one of deviance, violence, financial irresponsibility, and sexual debauchery.

Failing schools don’t equip these (often) poor student audiences with the tools to realize this sociocultural cycle as harmful and dangerous, and so many of them continue to support.

Then, some claim Black people don’t support artists. The pinning of non-support of artists on Black people is elitist pish-posh. Blacks still buy albums and flock to concerts in droves. Pirating is a Western problem, not a Black problem.

Expectedly, wealthy White owners of Black culture avenues know this—and play on these stereotypes. They’ll blame the cultural consumer for the lesser financial success of artists who speak of racial pride, social injustice, and the ills socioeconomic structure. Or they’ll explain that they’re “giving the people what they want to hear” when they excitedly sign the next young rapper feeding teenage crowds sexually violent lyrics in catchy tunes over rhythmic beats. But, what people?

While patriarchy, sexism, misogyny, homophobia, and self-hatred run rampant in Hip-Hop and rap music, culture critics mustn’t forget to question the maker and the medium. As a culture critic myself, I take heed to the relationships between the dollar, the product, and the distributor. Left un-policed, these forces often intertwine into tightly-knit knots of cultural appropriation and the turning of the hungry Black artist against his or her own people in pursuit of the dollar. Though Black people can (and do) wield class privilege, racist corporatist systems move in bigoted, economic silence, buying up cultural distribution neighborhoods in droves and driving rich Black art to tiny project ghettos, where they must work ten times harder for a tenth of exposure or profit. Call it musical gentrification.

Or, call it the greatest cultural kidnapping on Earth.

The White dollar and its partners in crime—privilege, racism, and wealth—orchestrated the greatest conspiracy in film, music, and television. The abduction of rich Black art. Her illegal confinement to a dark, dank cellar under the gaudy mansion, where lyrics about Emmett Till and ravaged vaginas eat, sleep, and bathe above her head. All because these vile lyrics assume the flunky position in the racist neighborhood, staying silent about the injustices that go in its backyard.

Then a lie was fabricated. An elaborate lie, about how she starved to death at the hands of abandonment, by her own people. That lie, then circulated by the elites, was accepted as supreme truth by the masses. And so she may suffer, but she is not without hope. She isn’t “demised”. She isn’t dead.

In the grand scheme, the joke is on the abductors. A few of us know the truth. And we’re snitching.

Asia Brown is a freelance writer, author, and indie book publisher. Brown House Press, her publishing company, relaunches this spring. On June 1st she'll premier a new, social-activist blog, Womanisted.com, that'll include original commentary, essays, and content honoring cultural nuances in feminism and womanism. Asia's 2nd novel, White Girl Hair, debuts on July 6th. She is currently attending the University of North Carolina at Charlotte for a Master of Arts degree in communication, specializing in rhetoric, media, and cultural studies.

No comments: